Eu me assusto quando vejo tanta gente se envolvendo com o futebol, e de maneira irracional, tomando decisões enquanto dirigente.

A paixão deve existir no esporte, óbvio. É por causa dela que as pessoas acabam entrando no meio. Mas cada um deve ter a sua função e suas responsabilidades.

Digo isso pois vejo: o Corinthians, beirando incríveis 3 bilhões de reais em dívidas, festejou a Copa do Brasil e, para muito aficcionados, “que se dane” quanto deve, pois o que vale é o troféu! Ao mesmo tempo, o Flamengo, atual Campeão da Libertadores da América e do Brasileirão, com receitas recordes e dinheiro em caixa, é criticado na Rodada 1 do Brasileirão por perder do São Paulo no Morumbi.

Pode?

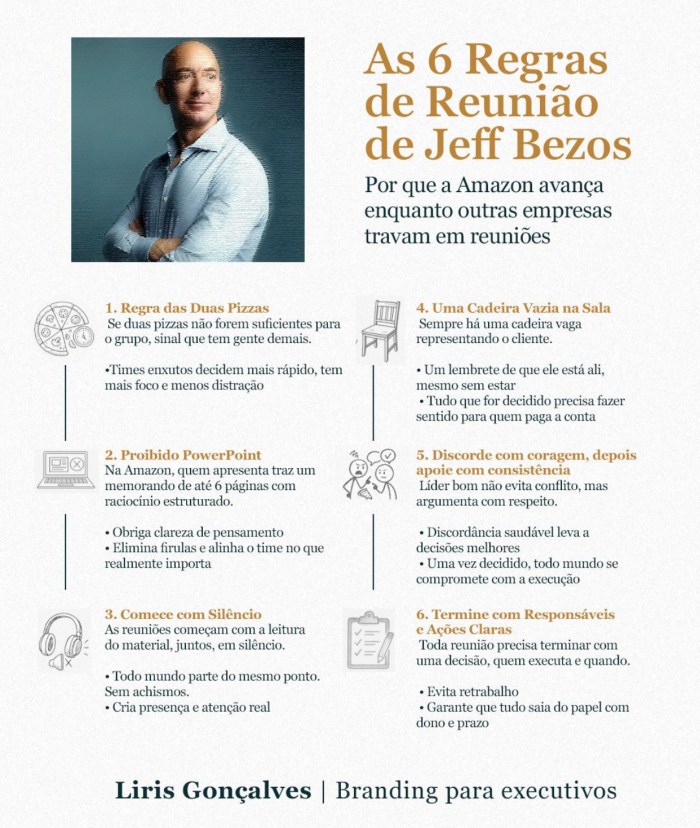

Torcedor, que não tem compromisso com várias nuances e só quer farrear, pode. Jornalistas, dirigentes e demais pessoas responsáveis do meio, não. Precisam, de maneira racional, pontuar as críticas momentâneas, os erros de um jogo e a fase específica. Mas ir do Céu ao Inferno em praticamente 45 dias, não dá!

Meu amigo Adilson Freddo, da Rádio Difusora, sempre diz: “O que vale para o torcedor de arquibancada é o resultado. A diretoria pode ser ruim, o time estar quebrado, mas se ganhar, tá tudo bem; o cara só vai se incomodar de verdade é quando o time perder”.

Assino embaixo. Precisamos tomar cuidado com esse cancro do futebol brasileiro: a cultura resultadista! O placar é o que vale para muitos (o que não deveria ser). Enquanto isso, a administração, o desempenho em campo, a estrutura… se tornam meros detalhes.

Mais razão na gestão, para o bem do esporte.

/s.glbimg.com/es/ge/f/original/2014/04/29/miguelaidar_ae_feliperau_690.jpg)